By Yamila Castro - Communications lead at Cities Alliance.

Climate change, conflicts, and poverty keep pushing millions of people to move from rural to urban areas in search of better livelihood opportunities. Rapid urbanization and increasing population growth are causing massive urban expansion, particularly in secondary cities in low-income countries.

This expansion is mostly disorganised - in Sub-Saharan Africa, 80% of the residential areas developed over the past 25 years are unplanned and informal. This poses serious socio-economic, developmental, and environmental challenges, while also bringing about some important opportunities for cities.

The economist and Nobel laureate Paul Romer spoke with Cities Alliance about urbanization and the need for “Making Room” in cities. This is a simple and cost-effective approach to planning for orderly urban expansion, which involves securing land for public space and an arterial infrastructure grid. The approach was developed with the New York University Marron Institute of Urban Management.

In terms of urban expansion and migration, how can cities realistically work on urban expansion planning in places where informal urbanization has already taken place?

Once you have disorganized informal settlements, the costs of remediating are very high. We used to say it’s 10 times more expensive if you don’t plan for it first. What every country and every city needs to do is to recognize they’ve got a backlog of problems that are very expensive to solve, then do something about it and ensure they don’t keep making more of those. Every time there is money to remediate an informal disorganized settlement, you should also spend some money on planning for expansion and making room so that the new expansion that comes won’t be disorganized, will be functional and much less expensive to create.

Many fast-growing secondary cities have limited budgets and only a few land-use planners. How can urban expansion planning help cities plan better with the limited human and financial resources that they have?

This is what was innovative about the work that Solly Angel (Urban Expansion programme director at NYU-Marron – Ed.) was doing. He came up with a kind of planning that avoids increases in costs, is relatively simple, and that every city can implement: laying out the arterial road network. People in every city and every local government know how to survey and plan for roads. Before urban development takes place, the arterial grid should be identified, you put stakes in the ground and protect that space. As development comes you can ensure to make room for transportation, water, electricity, and communications. Those arteries are the way to connect all the necessary infrastructure. You don’t have to do an enormous amount of planning upfront. This is a very minimal level of planning that can save 10 times the cost.

In places where urban growth has already happened, how can international development partners support the scale-up of this planning approach?

We need to accept the fact that cities will get bigger. Many officials don’t want their cities to grow and they think that by passing a law they won’t. This is unrealistic, it’s just a guarantee of informal settlements and it’s also inhumane. It’s terrible policy.

What policy should be about is to make room for those people who want to move to the city and benefit from the opportunities that cities can offer.

When it comes to ‘making room’, particularly in the case of migration, local authorities often face a lack of resources for those who are already in the city, which makes it difficult to provide for newcomers

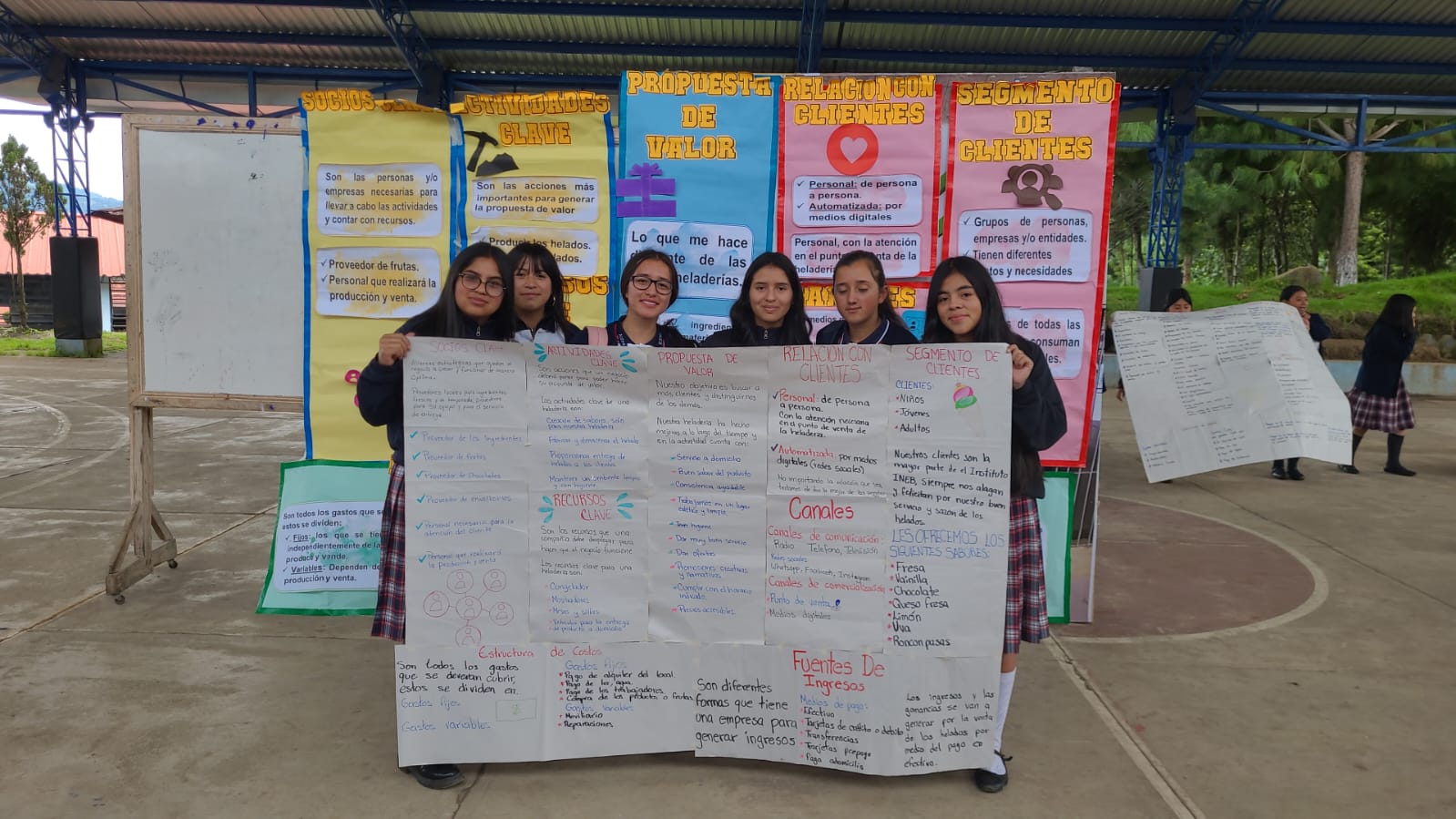

When we spoke to mayors in Ethiopia and Colombia, some of them could see the advantages of this approach for their cities. What you have to think of is that migrants to cities are not burdens, they are not charity cases, they are people who want to work. If you let them come and work, they will generate economic activity, that becomes part of the economic base that the city government can rely on to finance things like public services.

Another important factor is that transfer payments and fiscal responsibility have to stay with national governments and money should follow people. We make often a mistake by saying we need to tax the more successful citizens to provide resources for the poor ones. But if that’s the arrangement, the citizens who are more affluent want to keep poor people away, they don’t want to bear the additional costs of social services. Infrastructure should be the responsibility of local governments but health, education, should be paid for at the national level. This will also foster the right type of competition between cities and these are the kind of cities we want to see as engines of economic growth.

Migrants to cities are not burdens, they are not charity cases, they are people who want to work.

Secondary cities in low-income countries struggle to provide an environment that fosters income and job creation for the growing population. How does urban expansion planning support investment and job creation?

There is nothing about our approach to urban planning that explicitly plans for the economy. And the point is, you don’t need to. If you look at a typical informal settlement, all kinds of economic activity take place automatically. People engage in construction; some people start providing food services and small shops. The important point about economic activity is that if you just let people work, they will find ways to work together and produce what they want. You don’t need to plan for jobs, you don’t need to have a government manufacture jobs. What you need though is to let people have a legal place to live, let them have transportation, so they can get from where they live to where there might be jobs and then let potential employers come in.

Would this not be a more informal approach to economy?

Informal economic activity is better than no economic activity. It is better to formalise so that people contribute to social security systems and so forth, but it’s better to have informal activity than no activity at all. What are harmful are disorganized informal settlements, because they make it impossible to get the land you need to lay a sewer or a water pipe or to establish a bus route. I draw a distinction between informal economic activity as opposed to informal settlements.

It’s better to have informal activity than no activity at all.

But they usually go together, people who live in the informal settlements, work in the informal economy

Yes, but that’s because of a policy failure! You could have formalised settlements at least in the sense that there are stakes in the ground that show where the road would be and where people can go to settle. You could have that kind of settlement and informal economic activity where the government is playing a very small role. It could even be an informal settlement where inside the defined and protected arterial grid the settlers decide on their own where their plots, the streets, and alleys are. Yet the government still has the land it needs when is ready to connect public services and this makes all the difference between a settlement that will be dysfunctional and a settlement that will grow into a modern successful urban area.

Given the huge impact that climate change has on migration and urban growth, how can cities better include climate preparedness and response into urban expansion planning?

The best way to address environmental problems is to help a nation or society become wealthy. Effective, successful economic development is the best strategy in the developing world. At the same time, it’s the rich countries that are producing most of the carbon and who need to take the steps to reduce emissions. I think it is both short-sighted and doomed to fail if we try to force poor countries to not emit carbon when what we should be doing is reducing emissions in the countries that are emitting so much. You also need public space - the government needs to control land that can be used as it sees best fit in 5, 10, 50, 100 years. We see many informal settlements developing on riverbanks which is very unsafe and damaging to the environment. The land for public space that the government should protect involves the grid for connectivity and infrastructure, the environmentally sensitive areas, and ideally the public space for parks and other amenities.

It is both short-sighted and doomed to fail if we try to force poor countries to not emit carbon when what we should be doing is reducing emissions in the countries that are emitting so much.

What are the major obstacles to future sustainability in low-income countries in the context of current urban growth trajectories?

Frankly, an enormous amount of bad advice on urban planning, from the rich countries to the poor. When looking for advice, local governments from poor countries end up often with a long list of things they are supposed to do next. It’s impossible and makes no sense. The western approach is not simple enough, does not focus on priorities and look at things people don’t need now, which is look at the places where there are no settlements yet and put stakes in the ground to mark it as part of the public space that the government will need in the future. You don’t even have to take possession of that land, but make sure people don’t build, don’t settle on it. People live on right-of-ways or riverbanks because they have no other place to go. As development takes place and people become more successful, their demands will grow, and more complicated issues can be addressed then.

What policies, actions, and technologies can be recommended to fast-growing cities to leverage population growth for overall wellbeing and development?

Cities are valuable because people can make connections. The connections they make require a surface area for a grid for those connections to be established. It could be a truck, a water pipe, a sidewalk. That grid is the responsibility of the government. The key is to take ownership of that land before expansion takes place, to keep options open use public space for what is most important at a certain point in time.

But land is privately-owned in many places…

This is a part of a much bigger message that the world needs to understand right now - the market cannot do everything. We need governments that are strong enough to do their job, which is to facilitate the adoption of new technologies. But, for a city government to do its job it has to own a two-dimensional surface area for a grid, and without that, as evidence shows over and over again, it will never have a functional urban area. I am very encouraged by the pilot projects that NYU was able to facilitate in Ethiopia (supported by Cities Alliance - Ed.) and Colombia, in secondary cities. Some of the local officials and mayors are taking action. We need to help them understand how to do this in a very natural way. The choice is up to them.

iiiii

Paul Romer is an economist and policy entrepreneur, and co-recipient of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Economics Sciences. He has spent his career at the intersection of economics, innovation, technology, and urbanization, working to speed up human progress. His title is University Professor at NYU, with an affiliation in the School of Law. Before coming to NYU, Paul taught at Stanford, and while there, started Aplia, an education technology company he later sold to Thomson Learning. He earned a Bachelor of Science in Mathematics and a Doctorate in Economics from the University of Chicago.

Related content

How They Do It in Ethiopia: Making Room for Cities to Grow

The Challenge of Rural-urban Migration and Urban Expansion in African Secondary Cities