Throughout the day, she sells the clothes popular with women in much of Somalia, Ethiopia and Djibouti, while working briskly alongside her daughter Amira – however, the shop wasn’t always a part of their lives.

Living precariously in an informal community of tin- and plastic-roofed homes on the outskirts of Jigjiga, they had no income until recently. But when an opportunity to learn business skills through Jigjiga University (JJU) presented, Waris seized it as a way forward.

"I saw this training as my chance to create a better life," Waris says. In short order, she learned how to set up a business and manage loans, as well as strategies for saving. "Before, I had no concept of the principles and characteristics of business and entrepreneurship. The training completely transformed my life-from a housewife with no income to a business owner," she says.

Five months after completing the programme, she borrowed start-up capital from her relatives and opened her clothing stall. Amira, who had been unemployed, began to work with her. "Together, we've learned to calculate profits properly and avoid losses," Waris says.

I can feed my children and pay school fees ... It brings me immense joy.

The partnership has brought vital financial stability to the family, although for Waris, the transformation is also deeply personal: "This means everything — I'm no longer dependent on others. I can feed my children and pay school fees," she says. Seeing her daughter employed and contributing to the family business is especially significant: “It brings me immense joy," she says.

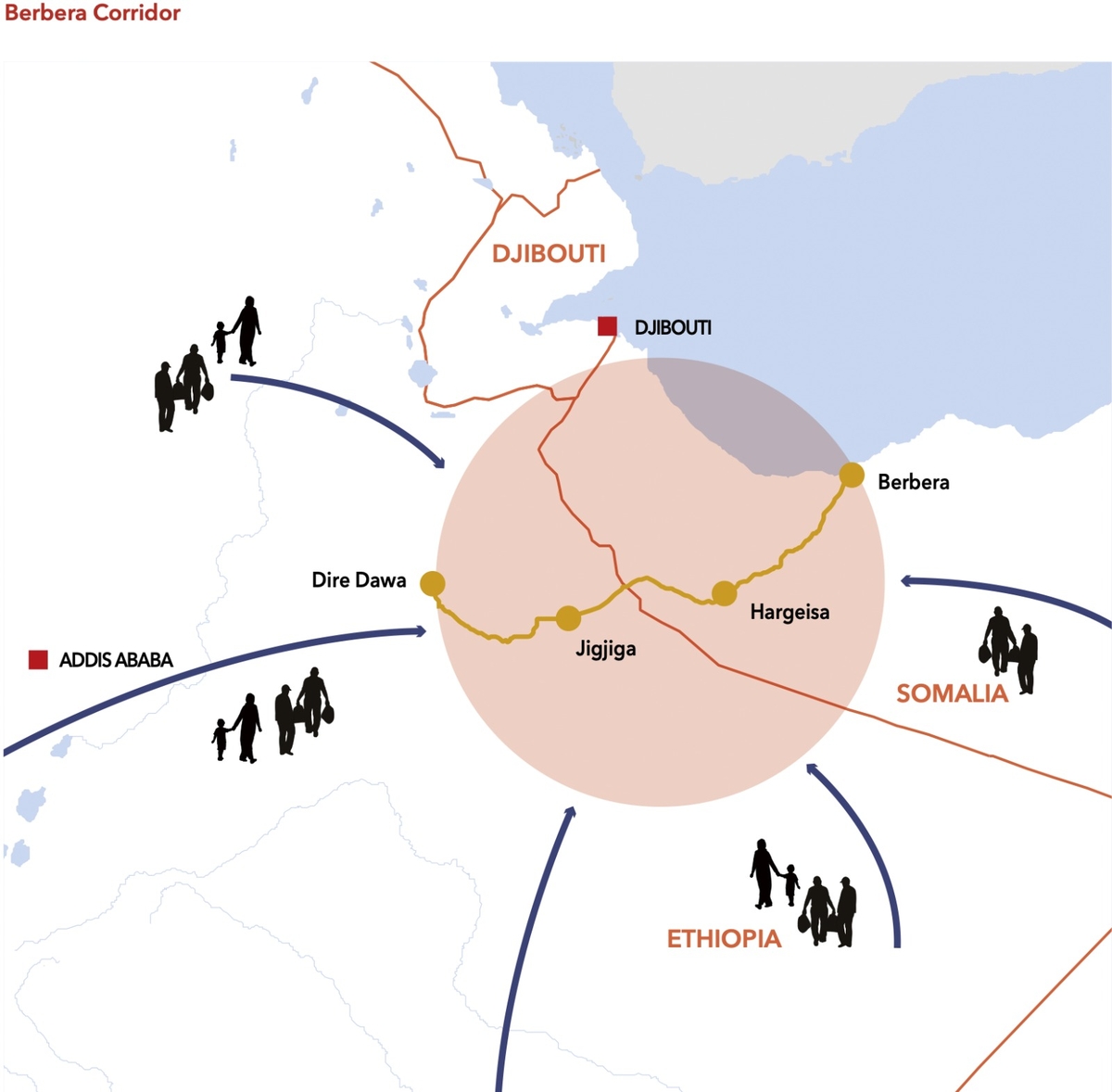

A fast-growing city of more than 800,000 people, Jigjiga straddles the Berbera Corridor linking Ethiopia’s landlocked capital Addis Ababa with Hargeisa and the Red Sea port of Berbera. The dynamic region has experienced significant growth in recent years through investments by the Somali diaspora and returnees, as well as notable migration flows driven by conflict and climate change.

Rural-to-urban labour migrants, refugees and internally displaced people like Waris and Amaris make up a significant part of the area’s population. They frequently experience poverty and exclusion, with women and girls disproportionately affected. The impact of the business training she received extends beyond Waris’s family to the broader community. "Many women like me have started small businesses,” she says.

The training has given local women the skills and confidence to start their own ventures, and now, they are supporting each other instead of remaining at home without income. "We've learned the value of patience in business and how to build good customer relationships. There's new hope in our community," she says.

In a fragile urban area where many displaced families struggle to survive in informal neighbourhoods often without power or water, these small businesses are lifelines for the women at their heart. "When women earn money, the whole community benefits, children eat better, families stay healthier and together," Waris says.

The JJU training is part of an innovative cross-border partnership between academia, local and regional government departments, donors and the private sector to improve the lives of some of the most vulnerable in the Berbera Corridor.

The city of Jigjiga co-financed land for local market spaces for the project, which is supported by Cities Alliance and financed by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) as part of the Resilient Systems of Secondary Cities and Migration Dynamics Programme.

It provides business and entrepreneurship training for migrants, the forcibly displaced and vulnerable young people in the host communities. Among more than 4,000 recipients of the training are new entrepreneurs selling clothes, running grocery shops out of their homes, and selling bottled water in communities that don’t even have a standpipe.

Most of those taking the courses are women, although not all. Aafi Qasim Abdulahi, a widowed father of seven, had struggled for years to provide for his family in their fragile host community. His previous ventures had failed, largely due to a lack of essential business knowledge, he says. When JJU offered him entrepreneurship training, Aafi seized it.

After learning how to raise capital, develop a business plan and manage loans, he launched a bottled water distribution business serving an area between Dagahle town and Jigjiga City. He went on to expand his business, opening a shop in Jigjiga's Taiwan Market with an investment of 40,000 ETB (around US$300). Aafi also employs his son in the business, ensuring that it directly benefits his family.

I started applying lessons on marketing, loan repayment, and saving, which transformed my business.

"The most significant change for me was the improvement of my business and mindset. I started applying lessons on marketing, loan repayment, and saving, which transformed my business operations," Aafi explains. His mindset shift didn't stop there. He also quit chewing khat, a frequently addictive stimulant, and became an example of how personal change can have a positive ripple effect locally.

"When one person changes, others notice and are inspired to make similar changes. It promotes empowerment, and that's how the community improves," he says.

His story, and those of Waris and Amira, highlight how entrepreneurship training can not only improve an individual's life but also inspire others to seek opportunities for growth, ultimately taking the benefits wider.